Work

The literary and intellectual world

Chesterton’s literary and intellectual world can be assessed through the Victorian heritage of great writers and novelists he admired and by whom he was influenced, like Charles Dickens, Robert Browning or R. L. Stevenson, or of earlier ones like Walter Scott and William Blake. He shares the radical spirit of reaction of some Victorians –like Dickens, Ruskin or Carlyle– against the excesses of the Second Industrial Revolution, but also of the 18th century publicist William Cobbett, who, through his campaign in favour of rural owners, will provide one of the bases of agrarian-oriented distributism. Dickens was undoubtedly his favourite author and with whom he identified, both for his condition of popular novelist who succeeded in getting through to the reader and for his social justice ideals, embodied in his novels. He defended the popular novel, which he engaged in with his detective literature, and he exercised social and literary criticism from an anti-intellectual, even radical and romantic up to a certain point, stance. Closer to the 19th than the 20th century, Chesterton’s work is pervaded by a Decadence movement atmosphere and medieval traits typical of the turn of the century.

The journalism

A brilliant polemicist, he indicated this aspect of his character in the spiritual, political, literary and, especially, journalistic fields. He contributed many years to the liberal newspaper Daily News and to the Illustrated London News, with a weekly column from 1906 onwards. Chesterton’s media facet must be considered as an extension of the essayistic one. As editor-in-chief of G. K’s Weekly (1925-1936), which he founded himself, he confronted through his articles the English powers-at-be. He didn’t, either in the journalistic or the literary domains, turn down any confrontation with contemporary English authors, particularly H. G. Wells and G. B. Shaw, with whom he engaged in significant controversies on questions of a moral, social or literary order. He became, thanks to his extraordinary talent with the pen and the atmosphere of dialectic freedom in which he played a part, one the most famous English writers overseas. In Catalonia he was greatly admired and developed friendships within literary and journalistic circles which fostered, during the 1920’s and 1930’s, the translation into Catalan of part of his work.

Chesterton, a man of his time

He has been defined as an engagé journalist for his commitment to the intellectual debate, a commitment he made extensive to all his literary work. Chesterton didn’t spare himself any discussions or controversies with the writers and journalists of the age, from H. G. Wells to Bernard Shaw, from the MP Charles Masterman to the editor of the socialist weekly The Clarion, Robert Blatchford, and in later years he also made his voice heard on radio. His radical nonconformist attitude spoke out against matters as important in early 20th century Britain as imperialism or eugenics. In this day and age he would be considered an influencer in the years between the 1910’s and the first half of the 1930’s, since he put the common man at the centre of all the political and social battles being fought in the middle of an economic and moral crisis, and amidst a crisis of parliamentary democracies. Against the backdrop of the failure of big capitalism and fear of bolshevism, and amidst the rise of totalitarianism, he opted for a third way by giving shape to a social democratic ideology based on English authors of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as the social doctrine of the Catholic Church formulated by Leo XIII.

Chesterton’s original work

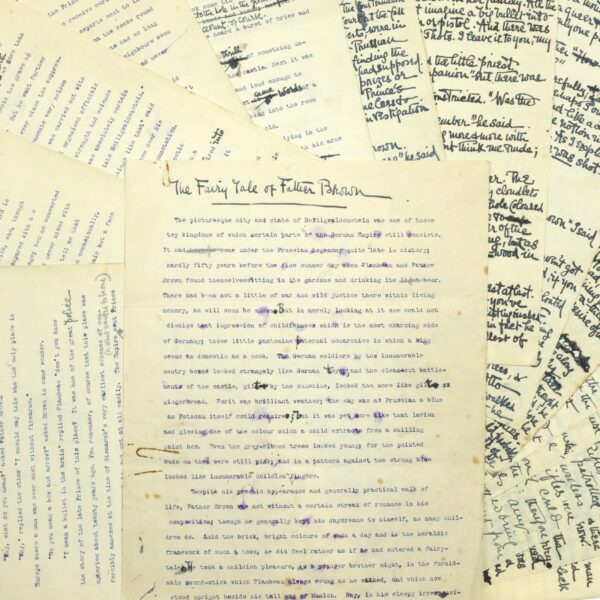

Manuscrit de The Fairy Tale of Father Brown

There is a certain consensus in considering that Chesterton wrote his best original work before 1910. His best essays on social matters (Heretics, 1905; What’s Wrong With the World, 1910), a spiritual autobiography and great essay on Christian thinking like Orthodoxy (1908), and, from the same year, what is considered to be his best compilation of detective stories, The Innocence of Father Brown, all date from this period. His writings on Charles Dickens are noteworthy when it comes to literary criticism. A good part of his work is buried under the thousands of articles he published in newspapers and magazines and are currently being brought to public attention through several compilations. He’s the author of an autobiography which appeared posthumously (1936), has been republished and translated to many languages and can be read as an introduction to his life, work and thinking. The literary might of his writings, whether in the press, as essays or fictional, make of Chesterton one of the more important authors of universal literature.

Chesterton on his work

In his posthumous Autobiography, Chesterton explains himself and his work in terms of a path through life. He unveils his childhood memories through family scenes and his father’s literary ascendancy, the streets and neighbourhoods which formed the landscape of his daily life, his relationship with friends and foes, as well as plenty of subjects reiterated in the lengthy controversies in which he took part and echoed in many of his other works. Nonetheless, it’s mostly his battle against the pessimism and scepticism ever-present during his formative years that pushes him to write and leave a mark on his time. Chesterton tends to reveal himself not only in his autobiography but throughout his entire work –whether through journalism, essays, biographies or fiction–, which must be understood as a whole that cannot be untangled from a literary universe which totally influences a romantic and idealistic world view, strongly rooted in Christianity.

Chesterton on literature

Chesterton was Charles Dickens’s (of whom he prologued the Everyman’s Library editions) first great vindicator and the Victorian novelist with whom he most identified, for his vision of the common man and for his use of the romantic novel which gets through to everyone. Chesterton always defended a popular type of literature, exemplified first by Dickens, but also by the authors of detective –a genre he cultivated himself with success in the Father Brown stories– or adventure novels (like Walter Scott of R. L. Stevenson, two authors he really admired). Reluctant in regards to the realist or naturalist kind of novel (such as Zola’s, for example), he decided on a romantic and idealist-based literature and the vindication of legends and fairy tales which, ever since his childhood, had initiated him in a world of transcendence, just as Shakespeare’s or other great authors in world literature’s works did when his father staged them on the toy theatre he had at home.